While their aerial counterparts are still primarily in the conceptual phase, the technology to not only build, market and sell but put driverless cars on our streets is already here.

In fact, the Boston Consulting Group estimates that, by 2030, nearly a quarter of “all miles driven” in the US will be from shared self-driving cars. ABI Research estimates that, also by 2030, there will be 11 million shared driverless vehicles on the road globally – or about 5 percent of the world’s traffic population.

The reality is, although questions of legislation, liability and ethics remain, nearly all major automotive companies have autonomous vehicles in the works, being tested and/or on the road. We’re nearing a time when driverless vehicles might very well become the majority. It’s important for municipalities to consider just how much this innovation could impact how (and where) we design our roadways, intersections and pedestrian crossings.

Below we look at the changes driverless technology will bring, the impact on roadway design in both urban and rural settings, whether autonomous vehicles will help or hinder traffic and steps you can take today in preparation for the innovative horizon.

Roadways of the present: built for human drivers, pedestrians

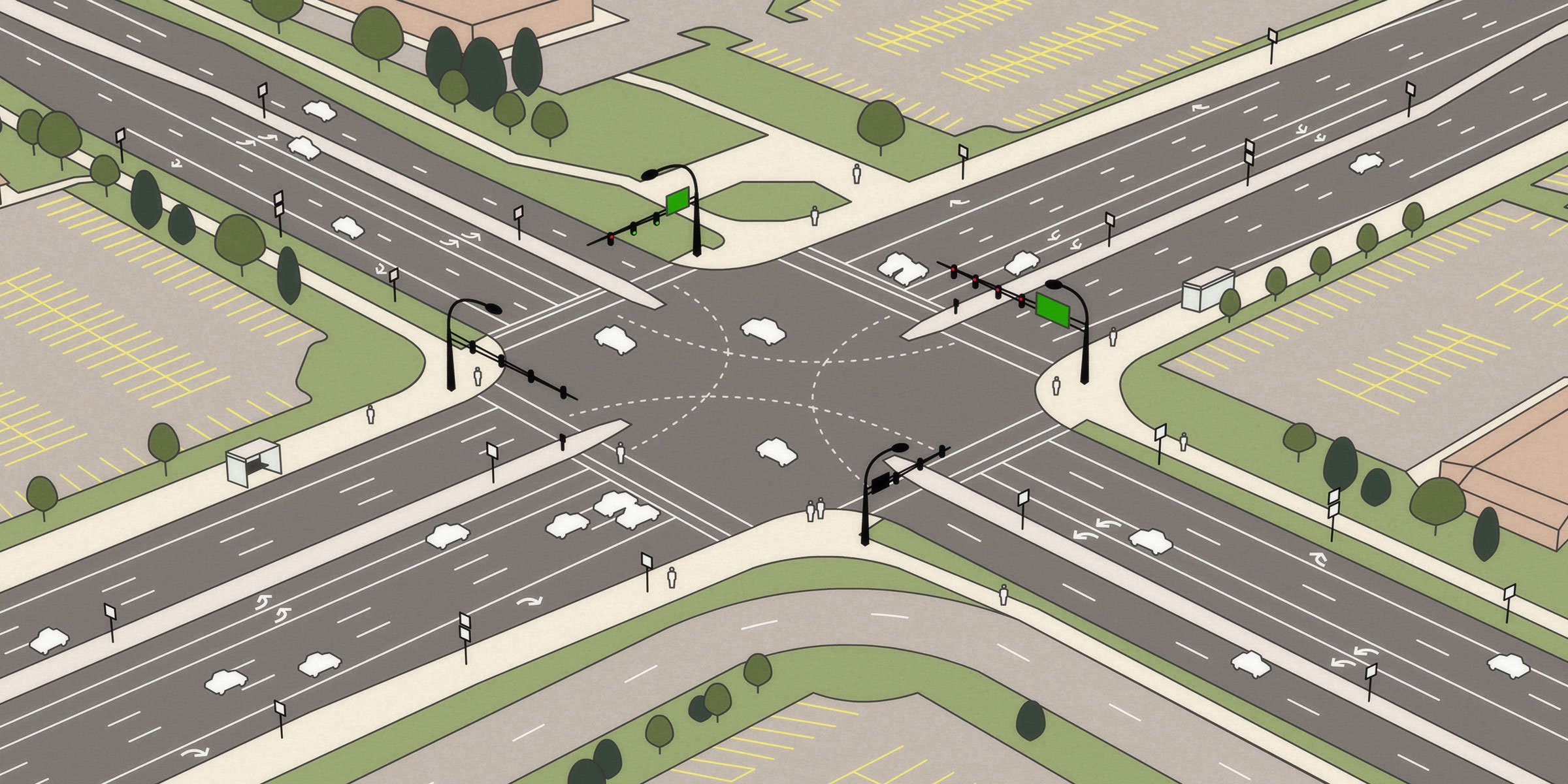

To understand how today’s roadways will change with the advent of driverless vehicles, it’s important to first understand the makeup of today’s roadways and intersections. Pictured below is a common intersection style found outside many metro areas: a four-lane with a six-lane divided urban highway.

The roadway and intersection are designed to move human-led cars and trucks. Timed signals guide cars safely along the corridor, which is designed to accommodate peak congestion hours. There are separate, dedicated turn lanes – each with their own markings – making a total of nine lanes, and measuring approximately 140 feet in width. As a result, and in order to accommodate pedestrians, refuge spots exist in the middle of each road for pedestrians who cannot make it completely across in one signal phase. The land surrounding the road is used largely for parking lots, which accommodate drivers visiting area stores and restaurants. Near the bottom of the illustration, there is a frontage road that provides local access.

This efficient and effective design makes sense for the early 21st century. But what about a future where “smart” vehicles are the majority?

How driverless vehicles will affect roadway design

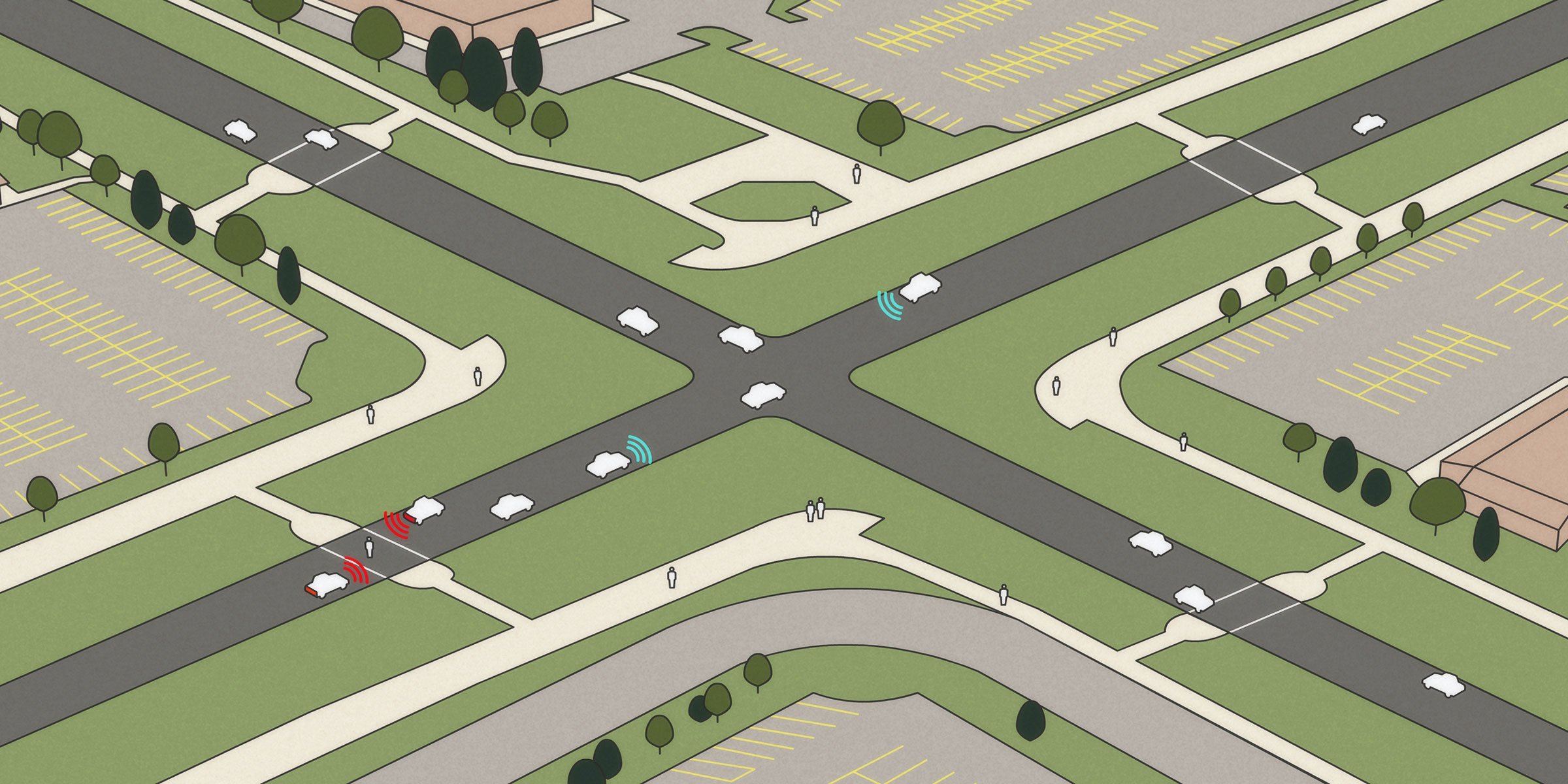

Interesting things happen to a road when we incorporate the anticipated capabilities of driverless cars into a redesign. The most obvious difference is a significantly reduced footprint and narrower right-of-way.

At first glance, a narrower road may seem illogical as the same, if not higher, traffic volume would demand a wide roadway. But here’s why this might not be true: if driverless cars have the predicted effectiveness over current drivers, the same traffic volumes could flow through a narrower roadway designed with narrower lanes and fewer of them. In fact, lanes likely wouldn’t need to be much wider than a delivery truck. In addition, when we can confidently rely on vehicle sensors and interconnectivity, there will be no need for the visual cues (e.g., road striping and signage) that human drivers rely on.

As also illustrated in the image above, the pedestrian crossings are moved away from the intersection. Today, for safety reasons, most pedestrian facilities exist at controlled intersections. Although this makes sense, it also requires pedestrians to walk extra blocks in order to legally cross a roadway. Since signalization is not necessary with driverless cars, crosswalks could be placed at the optimal place for pedestrians.

With algorithms, GPS and complex computers replacing road signs, traffic signals and smart phones (for GPS purposes), an unprecedented intermodal efficiency becomes possible. An efficiency that could significantly impact not only how we move, but also how and where we live.

Perhaps the first impact we’ll feel from the transition to more driverless vehicles will be the impact on surrounding land use and parcels. For example, with fleets of driverless cars operating like a modern transit system, able to pick up and drop off passengers 24 hours a day, parking lots could become obsolete. The land, then, would become available for any number of uses. Pedestrians and bicyclists would also play a much larger role in corridor design. Roadways that have become more pedestrian-oriented (as we see in Europe) tend to prompt more mixed-use, walkable development.

The steps cities, counties and towns can take today

Peering into the future is a fun exercise, but what does it all mean for today’s cities, counties and towns? What should engineers, city planners and municipalities do today to prepare for a future that might still be decades away?

1. Stay informed, be proactive. If expert predictions of 2020-2030 are accurate, we need to be proactive about how driverless cars might impact our communities. We also need to stay informed. For example, look no further than the State of Minnesota, which has established a Governor’s Advisory Council on Connected and Automated Vehicles (CAV). This Advisory Council – through facilitated sessions involving state liaisons, experts, stakeholders and the public – meet regularly to share ideas and feedback on how CAV technology will impact the lives of Minnesotans. By December 2018, this group is expected to prepare and communicate recommendations in statutes, rules and policies to the Governor and Legislature. Check your state and local governments, subscribe to various news outlets and join in on the conversation where possible.

2. Be intentional but realistic about the roadways you’re designing today. The Center for City Solutions at National League of Cities states that only 6 percent of US major cities’ long-range transportation master plans are weighing the “challenges” driverless cars will bring. Predictions are that cities will become more human-centered as technology continues to change our transportation; we’re already seeing this with the continued rise of “complete streets” design across the U.S. It’s important to understand that, despite the continued efforts to get driverless cars on our streets, and even if they do become the majority, roads will still need to be designed to accommodate human drivers. By planning corridors for a more equal mix of modes, we position our transportation infrastructure in line with present day trends while making it less challenging to accommodate what’s ahead.

The hurdles that still need to be climbed

As you consider the present to prepare for the future, much needs to be solved, or resolved, before driverless technology begins to dominate our streets:

1. State vs. Federal Legislation. Who has power to make policy – state or federal? If the states are handling policy development, where do jurisdictions end and can we travel cross country? How will regulations be made within each state to cover each of the following hurdles? Will we license the driver or the vehicle? What about insurance? Legislation like this is not a new challenge by any means; it was an obstacle experienced by the railroad industry when it first began.

2. Inclement Weather. So far, the driverless car technology doesn’t perform well in snow, fog or heavy rain. For example, according to Fortune, inclement weather including heavy, icy snowfall neutralizes some of the most advanced technology by blocking vehicle sensors. Extreme temperatures pose another challenge. Ultimately, significant strides are required before driverless cars can gain a tire-hold in northern climates.

3. Funding. Perhaps most important is the matter of funding. For example, at a project level, we can imagine far fewer road expansion projects. We can also expect a decrease in typical roadway maintenance – this being the result of fewer lights, fewer parking lots, less pavement and no pavement markings. However, the costs of the technology would balance the maintenance expenses. Especially in the beginning of this transition. More funding will be needed to install and support high-tech roadways, which might include digital technology in the pavement, sensored lights, among other components.

4. Safety. Taking your eyes off the road for just two seconds multiples your chances of collision by 20. And, 88 percent of drivers admit to using their phone in some capacity during a commute. The challenges human drivers bring are not new and will, in theory, be eliminated by driverless vehicles. But we will need to overcome an endless amount of safety concerns before there is comfort in committing to a driverless future. How can one promise and prove errorless technology? How will driverless vehicles interact with human-led vehicles? How will accidents be handled? These are just a few of the safety obstacles that need to be waded through.

5. Cybersecurity. In today’s digital age, malicious attacks are becoming more frequent and sophisticated. Often cited as the most vulnerable are IOT devices, which automate everything from our thermostats to auto-filling online forms. According to Forbes, none of these will cause as many cybersecurity “headaches” as autonomous cars and the complicated task of making them hacker proof. As just one example, recently a team of experts easily penetrated the car area network of a semi-autonomous vehicle before killing its transmission. It’s safe to assume engineers have and will continue to make strides specific to security, but the need for assurance remains a priority.

6. Traffic: Urban vs. Rural. In rural settings, the intersections are fewer, the populations less dense and the need for stops minimal. Experts believe this will significantly improve both ease of travel and traffic. However, in dense cities, the Chicago Tribune theorizes that the effortlessness and efficiency of traveling by way of driverless vehicles will “make traffic worse, not better.” One reason is our tradition of “single occupant” travel as opposed to carpooling; this could put more vehicles on the road more often, adding to traffic jams. Also according to the Tribune, “If driverless cars become cheaper to use per trip than taking the bus or streetcar, this could put more people in autonomous vehicles, further clogging the roads.” What’s clear is that policy, pricing and regulations will be vital when it comes to traffic.

Planning, especially when talking about the development of transportation communities, often gets described as looking into a crystal ball. But we also need to be realistic about how driverless cars will inevitably impact the transportation system and our communities.

Those of us in the transportation community need to have these conversations, remain proactive and informed, communicate what’s potentially ahead to our clients and begin planning for an entirely unique future. The future is here, let’s not ignore it.

About the Expert

Tom Sohrweide, PE, PTOE, is a senior traffic engineer, father and youth leader passionate about preparing the world for the next generation.

.png?width=113&name=SEH_Logo_RGB%20(1).png)