SEH Municipal Engineer Greg Anderson is often asked “Why does water remain on our streets after a rain storm?”

There are a number of reasons! Rainfall event probability, roadway speed, topography and other considerations come into play when a street system is designed and constructed. Each of these can affect why water stands in a roadway for a time.

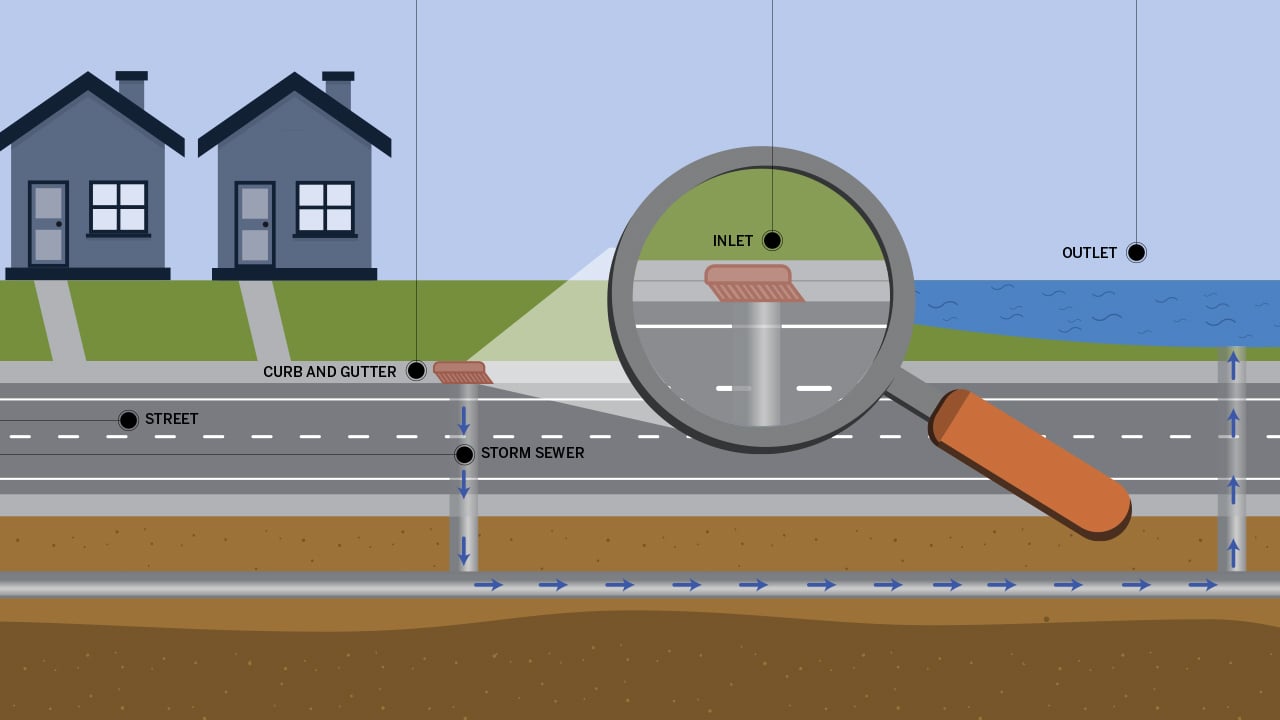

In residential areas with urban streets, stormwater is conveyed along paved roadways with curb and gutter and into the storm sewer system through inlets or catch basins. A catch basin takes the water off the street and into the storm sewer pipe under the street and eventually to the storm sewer system outlet. Outlets can be at the end of the block or several miles away and often end in a storm pond where the storm sewer system empties out.

Depending upon a number of factors, stormwater may stand in a roadway for a while after a rain event. Below, we examine a number of reasons why this happens.

Blockage

The street is part of the storm sewer system. Rainwater falls on the street, runs across the pavement to the gutter, and along the gutter to an inlet. A simple answer to why stormwater builds up in the street is that the inlet grate may be plugged with debris (leaves, sticks, grass clippings or garbage). Or, the pipe could be clogged under the street.

The water drains once the blockage is cleared. These blockages typically occur in the spring after a windy storm with heavy rainfall or in the fall when the leaves drop. An easy way to prevent this is to regularly inform residents to keep drains near their homes clear.

Probability

Street storm sewer systems (inlets, manholes, pipes and outlets) in most residential areas are typically designed for what’s commonly referred to as a 10-year, 24-hour storm event. A 10-year, 24-hour storm event is defined as a storm bringing approximately four inches of rain in a 24-hour duration. These storms have a one in 10 or 10 percent chance of occurring in any given year. Storm ponds are generally designed for water quality volumes and are evaluated at high water levels for a 100-year, 24-hour storm event. This is so the storm ponds don’t overflow in the surrounding areas. They are also designed for rate control to protect downstream conveyance and infrastructure.

10-year and 100-year events defined

There is a misconception when referring to 10-year and 100-year storm events (or any given number of years). These designations do not refer to storm events happening once every 10 years or once every 100 years. Rather, they refer to the probability of a storm event of that intensity occurring at any given time.

If stormwater is standing in a residential street, it is likely there was more rainfall than the system was designed to handle. The street will hold the extra water until it can make it in the system. In most residential areas with low volume, low speed streets (30 MPH or less), water standing in the street briefly after a significant rain event is not uncommon.

Roadway speed

On higher speed roads – like county roads and smaller highways – the storm sewer system design includes another factor: spread calculations. Due to the larger traffic volume (two or more lanes in each direction) and higher speed, the storm sewer design engineer takes into account how far from the curb the water from a given storm will “spread” toward the travel lane(s). These types of roads are typically designed with spread calculations of a three- to five-year event.

These storm events occur more frequently than the typical 10-year design. The reason for this is with the higher speed traffic, you don’t want standing water from the gutter reaching the travel lanes. This can be dangerous for the traffic (hydroplaning, driver surprise when driving into standing water, etc.). If you do see standing water in a roadway, don’t drive into it — choose a different route.

Pipe size/inlet spacing

Another way to keep water out of the travel lanes is by incorporating larger diameter pipes and more inlets. On higher speed roads, design engineers incorporate more inlets into the stormwater plan. More inlets closer together convey the water away faster.

Even when cities and counties know the best solution may be more inlets and larger diameter pipes, one variable can change the solution. Money. The larger the storm sewer system, the higher the cost of the project. This is why designing storm systems around the 10-year event has become industry standard for most local streets. It’s a good balance between the frequency of rain events and the cost of a large storm sewer system. Of course, there are exceptions to this rule. Bigger cities often design to larger rain events in downtown areas or other areas where they need to get the stormwater out of the street as quickly as possible.

More frequent/intense rain events

While the storm sewer system is designed to keep water out of the lane of travel during most events, it still occurs. However, according to the United States Environmental Projection Agency (EPA) recent years have seen more frequent and intense rainfall events. Based on data collected over the past 10 years, storm sewer design calculations are beginning to change to accommodate these more frequent and intense storm events.

Subdivisions

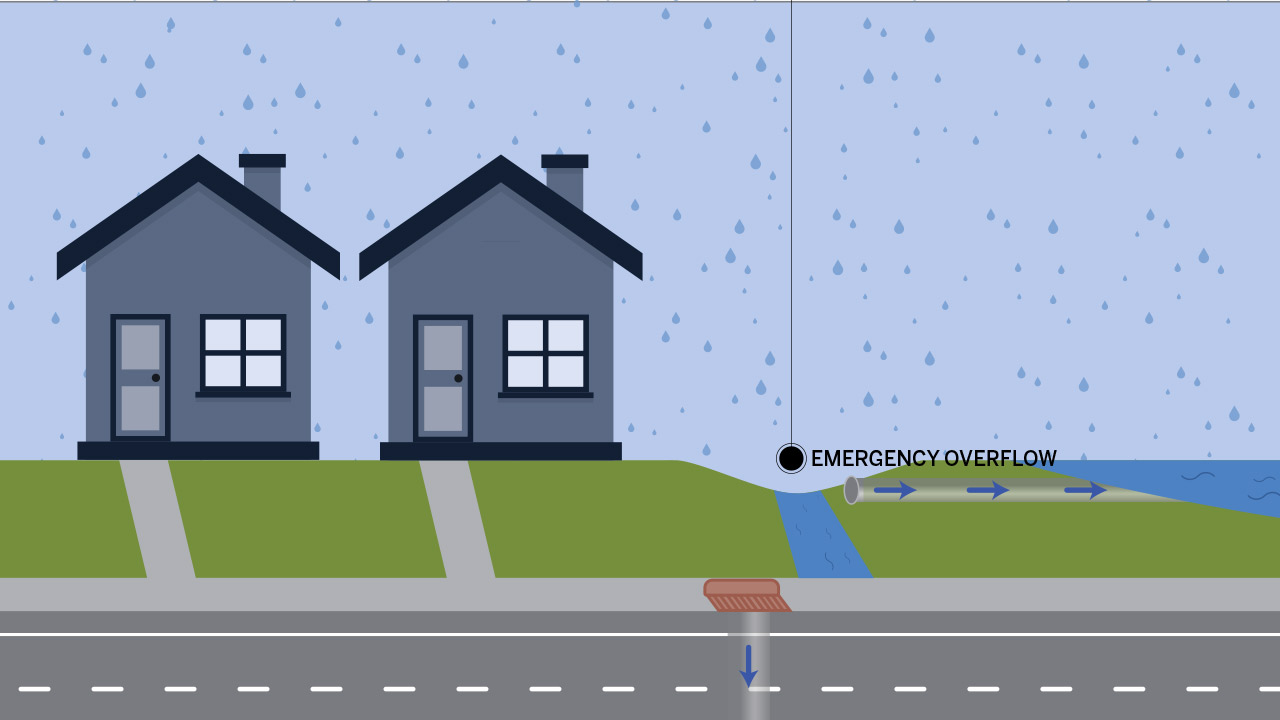

In a residential subdivision, most streets will have standing water in the street after a large rainfall event, but it generally should stay within the area around the curb. Most streets are designed to have a low point(s) where water from each direction of the street flows to the inlets. When the storm event exceeds the design and the water begins to fill the street, the street and adjacent yards at the low points are designed with an emergency overflow. Here, the water runs through the yards to a pond or swale instead of toward the homes. Sometimes, the street itself acts as the emergency overflow. In this case, the street will convey the water to another, lower point.

Summing it up

When we experience big storm events, people often ask why the rainfall doesn’t go into the storm sewer right away. It’s likely because precipitation amounts brought by the storm exceeded what the storm sewer system was designed to handle or inlets or pipes have been blocked. Larger pipes and more water inlets can take away more water, but at a cost. Design engineers have created standards by which roadways and storm sewer systems are planned. However, these standards are beginning to change with more frequent and intense rain events.

About the author

Greg Anderson is a municipal engineer* and storm sewer designer who understands the delicate balance between cost and effectiveness while making sure our streets can accommodate what’s ahead.

Professional engineer registered in MN.

.png?width=113&name=SEH_Logo_RGB%20(1).png)