Developing a capital improvement program (CIP) to guide future investments can seem daunting.

Funding sources, priority of needs, airport qualifications, as well as state, federal and local fiscal years all must be factored into the process. The following provides some guidelines to help determine what you need to include when starting a CIP, tips to streamline the process and other important considerations.

What is a CIP?

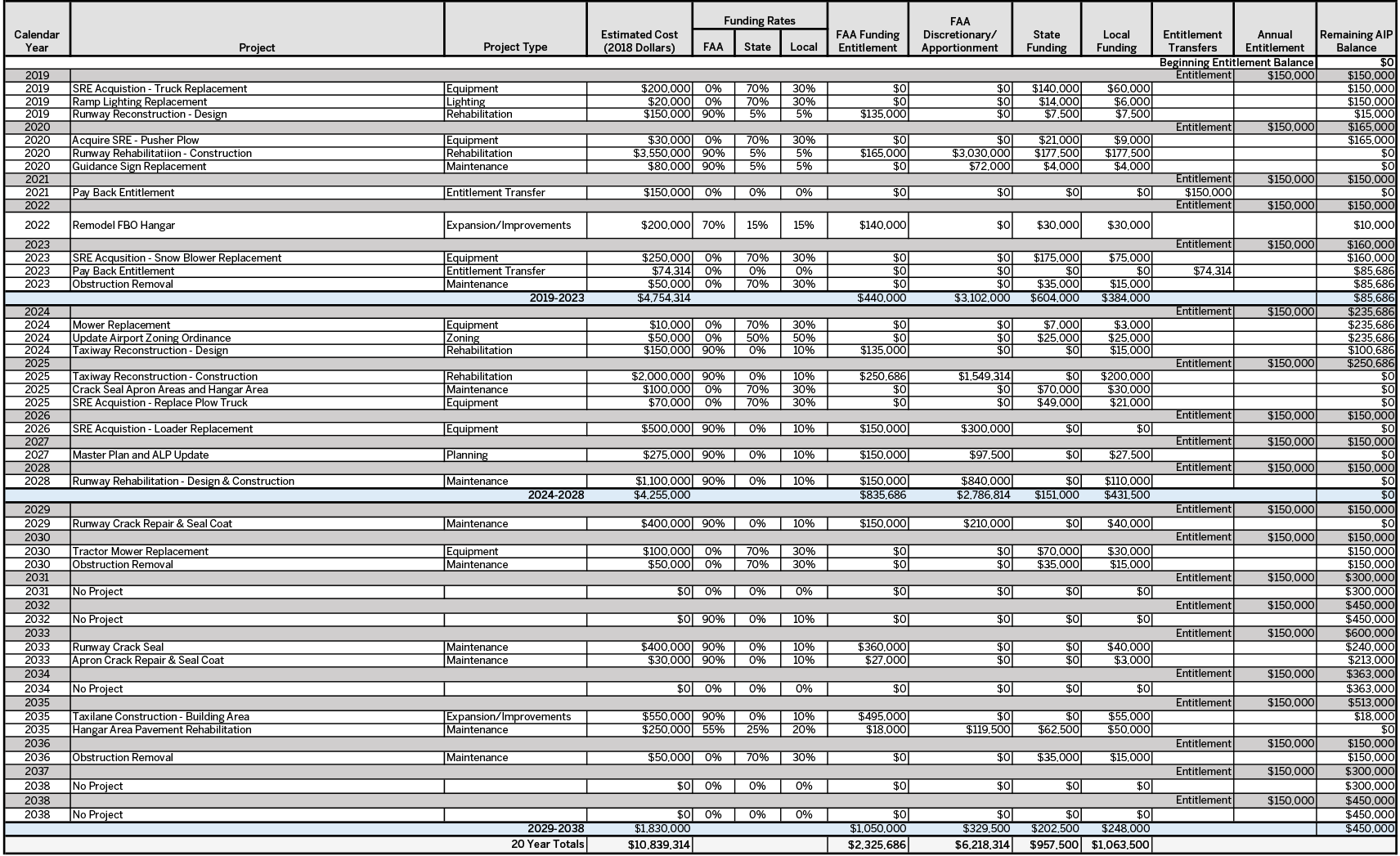

At its simplest, an airport CIP identifies project priorities and funding sources over a period of years and is used to plan for future projects and required funding needs. It is a document that serves as a planning tool for maintaining, developing or expanding an airport. Additionally, the CIP also serves as the basis for how the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) and state funds are distributed. If a project is not included in your airport’s CIP, it will not be considered for federal or state funding.

The FAA prepares a national CIP each year based on collective information gleaned from each of the nine regional CIPs across the U.S. Each region has an office that gathers the CIPs completed for the airports in their region. These regions include:

- Alaskan

- Northwest Mountain

- Great Lakes (includes Minnesota and Wisconsin)

- Eastern

- New England

- Central (includes Iowa)

- Western-Pacific

- Southwest

- Southern

Likewise, each regional CIP is assembled from information provided by individual state airport CIPs. To make sure funds are apportioned appropriately, it’s important to be in contact with your local department of transportation and FAA representatives early and often.

In order for a CIP to be most effective, you should include 20 years of projects. This helps to illustrate to your local and state governments the need for aviation funding. The U.S. Congress provides funding to many programs throughout the country. If Congress does not see a need beyond the next five years for aviation funding, they may use the money they have for other initiatives. It’s important for airport sponsors to show a need for funding into the future to continue to receive state and federal funding support for their airport projects.

But, we all know budgets and goals change. So, it’s important to review and update your CIP every year.

What to include in a CIP

A successful CIP includes five parts:

- The year the project is expected to occur. Make sure you're considering the federal, state and your local fiscal years and accommodating them appropriately.

- A description of the project. Include an easy to understand title of your project. Some states have other considerations to include in your project description. For example, in Minnesota, it is helpful to add the federal fiscal year you anticipate the project to receive a grant to the project name.

- The type of project. For example, is the project going to occur on the runway, taxiway, apron or access road? Is your project a planning project or for equipment?

- Total cost of the project. Cost is the most important element of a CIP.

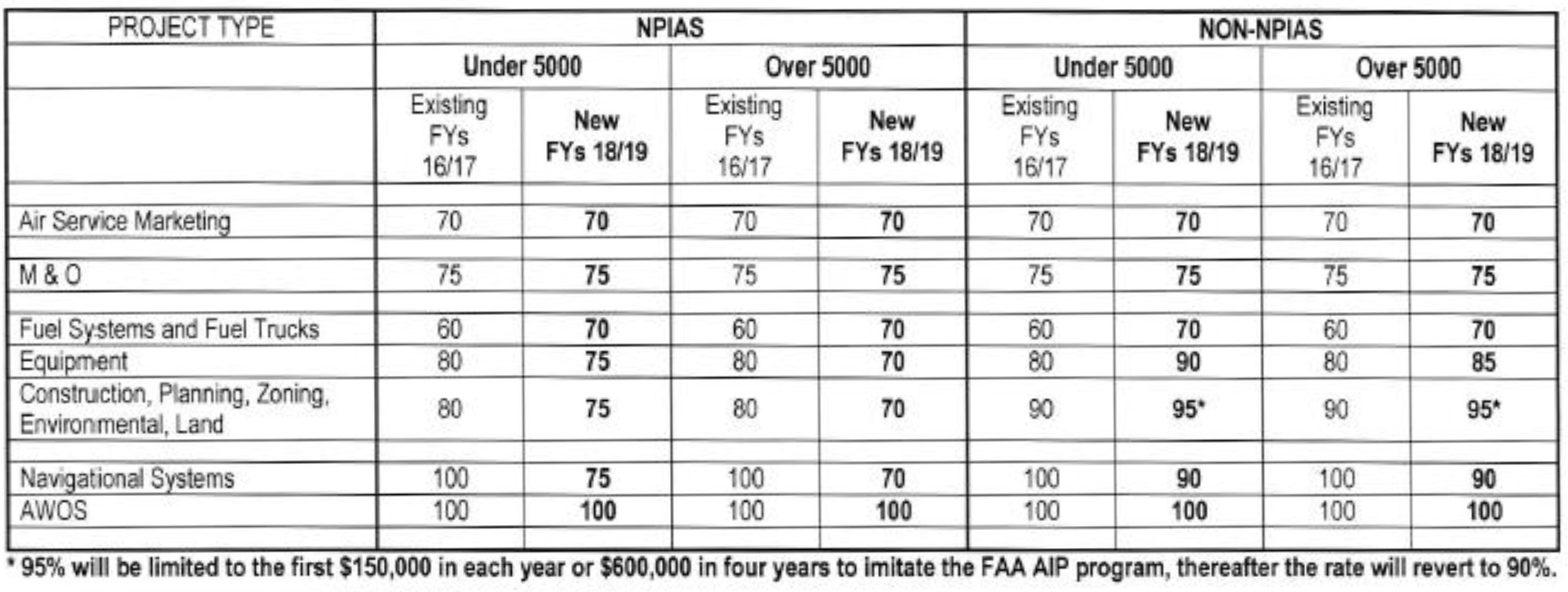

- Funding split. Projects eligible and justified for federal funding will most commonly be funded at 90% with federal grant dollars and 10% with local dollars. Some states also participate in the local share of projects. For example, the State of Minnesota provides 5% of the project costs for most federal projects, leaving just 5% of the total costs up to the airport sponsor. Federal projects need to meet the eligibility and justification requirements explained in the Airport Improvement Program (AIP) Handbook. Depending on the type of project, certain criteria need to be met to receive federal funding. In other words, just because you want a runway extension, doesn’t mean your project is justified or that it is eligible for federal funding.

Some projects funded only with a state grant might have various funding rates depending on the state and the project type. Coordinate early and often with your federal and state agency representatives to understand the funding split for your projects.

Airport classifications

Qualifying for state or federal airport funding options depends on how your airport is classified. Put simply, there are two basic types of airport classifications: national and state.

National Plan of Integrated Airport Systems (NPIAS). NPIAS airports are airports that are eligible to receive federal funding. NPIAS airports can be commercial service airports or general aviation airports. If they meet specific criteria, such as having at least 10 based aircraft or being at least a 30-minute drive time from another NPIAS airport, the airport sponsor can receive federal funding. The FAA AIP Handbook lists projects eligible to receive federal funding. The FAA prioritizes funding projects needed for safety (runway reconstruction, taxiway reconstruction, obstruction removal) and then other projects to maintain the existing airport infrastructure and provide facilities for the user needs of the airport.

Other projects eligible for federal funding include master plans, environmental assessments, snow removal equipment, hangar construction, access road rehabilitation and others. Meet with your FAA program manager often to determine eligibility and justification for your projects. Although the primary funding source for NPIAS airports is federal, they can still receive state funding for their projects.

State airport. State funded airports are those that are not included in the NPIAS but are included in a state aviation system. These are typically the smaller airports that receive state funding for eligible and justified airport projects.

Common Airport Funding Types

Airport Improvement Program (AIP) funding

The FAA AIP was created by the Airport and Airways Act of 1982 to assist in the development of a nationwide system of public-use airports. Amendments to the program since 1982 have consistently increased funding levels, participation rate, and eligibility.

The AIP has limits on eligibility. Generally, grant eligible items include airfield and aeronautical related facilities, such as: runways, taxiways, aprons, lighting and visual aids, as well as land acquisition, planning and environmental tasks needed to accomplish the Airport improvement projects. Some revenue producing items like fuel farms and FBO facilities may not eligible for AIP funds. Additionally, equipment eligibility is limited to safety equipment like Aircraft Rescue and Firefighting (ARFF) trucks and snow removal equipment (SRE). Mowers, earth moving equipment and airport operations vehicles are not eligible for funding. The FAA utilizes a priority system to rank development items. Generally, the smaller the Airport and the farther the item is from the runway, the lower priority it receives (e.g. runways have priority over taxiways, which have greater priority than aprons, which have priority over roads, etc.). However, development or equipment required by rule or law has a high priority.

There are two types of AIP funds that an airport may receive: entitlement and discretionary.

Entitlement funding is a main source of funding for general aviation airports. General aviation airports typically do not have scheduled passenger service and serve private aircraft, business aircraft and smaller charter aircraft.

Each year the FAA gives general aviation airports $150,000 to spend on justified and eligible projects. However, if the airport does not have a use for the funds, they can roll over the entitlement funds for up to four years, potentially banking up to $600,000. To access the funds, the airport must meet certain FAA requirements. Unused funds are sent back to the FAA for redistribution to other airports.

However, airports can do what are called entitlement transfers, where they roll unused funds over to other airports to use on their projects. If an airport decides not to do a project one year, they can lend all, or portions of, their entitlement funds to another airport within the state that is working on a project. The airport will then repay those funds back to the first airport in a specified year when it makes the most sense for both airports. By doing this, it keeps the entitlement funds within the state and avoids the funds going back to FAA to be used elsewhere.

Discretionary funding consists of leftover entitlements collected and redistributed nationally and is typically used on high-priority projects like runways and taxiways. Of note, discretionary grants tend to be awarded later and are usually not received until late in the fiscal year. State apportionment funding is similar to discretionary, but consists of federal funding given to the state to use, similar to discretionary funding.

State funding

State funding can include many funding types and rates. Examples of state funding are hangar loan programs and maintenance and operation grants. There are also vertical infrastructure funds and other state programs depending on which state your airport is located.

State bonding bill funds can be used in many states for airport infrastructure improvements. In Minnesota, a bonding bill is typically passed every even year. They require agreement from the state legislature and governor on how the funds should be spent, and bonding bill funds are not guaranteed until passed into law by the legislature.

There are also a number of miscellaneous grants that can be used. Two of the most common in Minnesota are the Department of Employment and Economic Development (DEED) grant and IRRRB grants.

All funding from both state and federal agencies must be for planning, design, construction or pavement maintenance projects, and cannot be used to supplement the operating expenses of the airport.

Local funding

Airport revenue and local general fund and tax dollars can also help contribute to airport project funding. Airport revenue can come from things like:

- User fees

- Ramp/tie down fees

- Landing fees

- Fuel sales

- Fuel flowage fees

- Land leases

- Hangar rent

- Leasing airport property for agricultural or farming purposes

- Mineral rights

With all of the funding options available and the differing times of year at play, it can easily confuse airport managers. Fortunately, there are a few things you can do to help streamline the process. The following tips can help keep everything straight.

5 tips to help streamline your CIP process

- Develop your own calendar – The calendar year is one of the hardest parts to figure out when developing a CIP. There is the calendar year, the State Fiscal Year and the Federal Fiscal Year – and none of them are the same. Do yourself a favor and develop your own calendar to figure out the best timing for putting projects on your airport’s CIP.

- Meet with federal and state agencies often – It is important to coordinate with your federal and state representatives, including the planner, environmental specialist and program manager, to best plan your projects and to determine if environmental work or other projects will push the year of receiving funding to a later date. For environmental and engineering projects, it is important to ensure all planning is complete prior to initiating and requesting a grant for these projects.

- Plan early and review your Master Plan and Airport Layout Plan (ALP) – Confirm with the FAA program manager that the proposed project location and layout shown on your ALP still makes sense with current guidance, especially if your ALP is older.

- Coordinate with local governments – Explaining the purpose and need for funding to your local government agencies is important. Making sure the local share of funding is available the same year as the federal or state grant is available is important for the project to move forward as planned. Bring your local governments along as projects are justified and ready for implementation.

- Put your projects on the CIP four to five years before you’ll need the funding – Just as it takes time for you to plan for your local share, the FAA and states need to plan for their share. It is important to have an accurate CIP for the near-term (five years), especially if you intend to use federal discretionary or apportionment funding. There may be other considerations that could drastically affect your project’s viability or timing. Understanding how your project will compete with other projects is important. Consider what airport component your project is (runway, taxiway, apron) and if it is a minor rehabilitation, major rehabilitation, complete replacement or new construction.

Calendar years vary widely

Because keeping up on all of the calendar years necessary in an airport CIP can be challenging in its own right, here’s a simple reference guide.

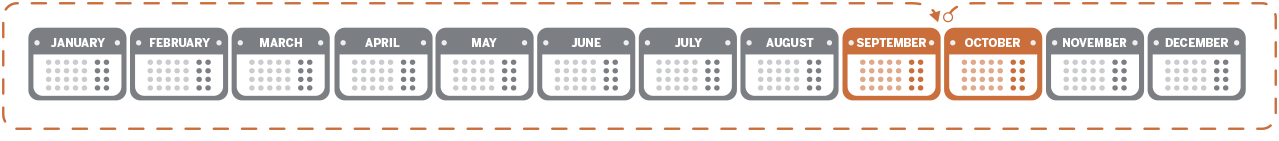

Federal fiscal year:

October 1 – September 30

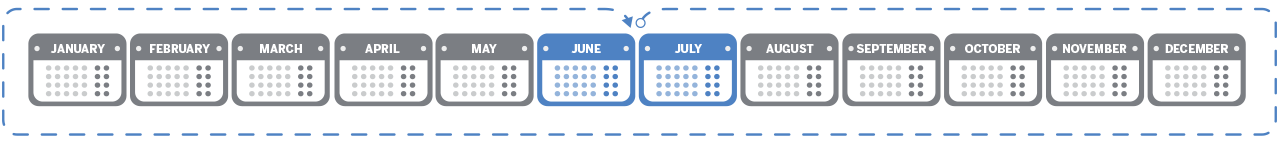

State fiscal year:

It depends on the state. Minnesota’s state fiscal year is July 1-June 30. However, in Iowa the state fiscal year shifts every year. Other states are also different. It’s important to understand and pay attention to those deadlines and stay in the know.

Local fiscal year:

Varies by airport sponsor (figure out yours to make sure)

Other considerations

Understanding project timing considerations and airport classification (federal or state funding) are important in developing an airport CIP – but here are a few additional points to consider when putting together a CIP:

- Is your planning complete for the project, and is it shown on your ALP?

- What environmental work needs to be completed before you can begin your project?

- What is the local funding balance needed for the project and what year will it be available to use?

- Have you presented your project to the decision makers and stakeholders for support and approval?

- Is your local department of transportation (DOT) and the FAA aware of your project?

- What type of funding can you use for your project?

- Ensure your airside needs are met for the next three years if you would like to start a landside project with federal dollars (hangars, fuels systems, snow removal equipment).

- How can you best phase your project to balance minimizing impacts to users and project cost?

CIPs guide airport funding

An airport CIP is not only a document guiding the future of your community’s airport, it also guides the funding of the airport and how it will function in order to meet project needs. It’s important your CIP is soundly prepared. Contact your DOT and FAA representatives early and often with your projects. Involve the local units of government, airport committee and/or board early to demonstrate the need and economic benefit of the local airport. Give them a vision so they can begin to designate funds for the local share of project costs.

To build a better foundation for Congress to continue to increase the allocation of federal funds to aviation, every airport should develop a 20-year CIP.

About the author

Melissa Underwood is a senior airport planner and project manager who understands through precise planning and forward thinking, any project is possible.

.png?width=113&name=SEH_Logo_RGB%20(1).png)