From diamonds and roundabouts to cloverleaves and directional stacks – each interchange type offers its own unique benefit.

The interchange has long been the main way to move travelers from one roadway to another. The concept was first patented in 1912. Since then, as more and more people use our roads, increasingly complex systems have been invented to accommodate them. To get a better understanding of this important transportation infrastructure, let's explore the diverse world of interchange design!

Service and System Interchanges

Starting with the basics, there are two main types of interchanges: service and system.

- Service Interchanges connect a freeway or controlled access facility (typically high-speed, high-traffic roadways) with local surface streets or arterials.

- System Interchanges carry traffic between two or more freeways or controlled access facilities via a network of ramps and connectors.

Here’s a closer look at each type of interchange along with the complex variations and the roles they play.

SERVICE INTERCHANGES

Diamond

A diamond interchange involves four ramps that exit and enter the highway. These designs are very economical because, compared to other options, they require less land and materials. The diamond interchange and its iterations are the prevailing service interchange design, and some of the first were developed in Los Angeles in 1941 along the Pasadena Freeway.

Tight Diamond

A tight diamond interchange has the same general form as the conventional diamond but the spacing of the design is tighter. The spacing between the two at-grade intersections (intersections directing travelers either onto or off the highway) is usually between 250 ft. and 400 ft.

.jpg?width=1000&name=Trunk-Highway-36-English-Street-Interchange_1280_001-(1).jpg)

Single Point Diamond

The single point diamond interchange, also known as a single point urban interchange (SPUI), first sprang up in 1974 in Clearwater, Florida. SPUIs have only one at-grade intersection on a minor road, and they tend to be more expensive than traditional interchange options due to the need for a wider and/or more complex bridge.

Diverging Diamond

The diverging diamond interchange (DDI), or double crossover diamond (DCD), was first developed in France and brought to North America around 2002. It is the latest new interchange form developed in the past 30 years, and because of this, it comes with a learning curve for many drivers. The setup is initially confusing because drivers must drive on the opposite side of the road as the roadways diverge; but once learned, this design yields significant safety improvements for both drivers and pedestrians. Click here to learn more about how a DDI works.

Partial Cloverleaf

Partial cloverleaf interchanges, also called “parclos,” use one, two or three loops for left-turn movements. Parclos are highly adaptable and can accommodate high traffic volumes. They are especially advantageous when one or more corners of the interchange must be avoided due to right-of-way or environmental restrictions.

SYSTEM INTERCHANGES

A system interchange controls traffic where two freeways meet. Unlike the service interchanges explored above, which exist at the intersection of a high-speed, high-traffic freeway, and a less-busy, lower-traffic collector road.

Cloverleaf

The cloverleaf design eliminates the need for traffic signals and keeps motorists moving. However, weaving is a problem that may lead to breakdowns in traffic and lead to more accidents. The cloverleaf was the first interchange design constructed in the U.S., and was built in Woodbridge, New Jersey, in 1928.

Directional

The directional interchange design often requires less right-of-way than a cloverleaf design. The primary disadvantage is increased cost because of the need for multiple-level structures. Directional interchanges are often warranted in certain urban areas where traffic volumes are very high and high-speed maneuvering is desired.

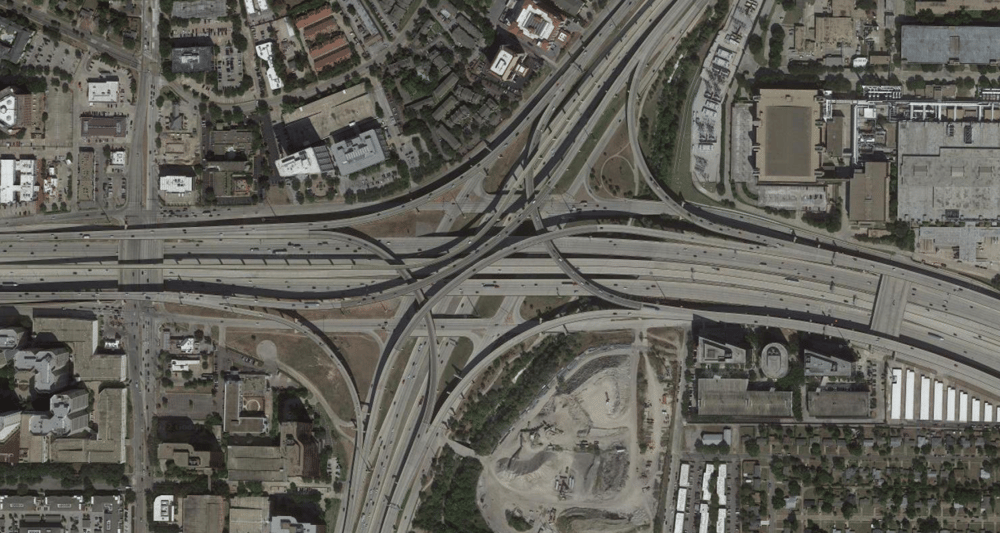

Stack

The fully directional stack interchange design eliminates the need for looping and weaving, making for easier transitions. However, they tend to be costly and take up a lot of land to implement. The first four-level stack interchange was built in Los Angeles around 1952.

One-of-a-Kind System Interchanges

Now that we've taken a look at more common examples of system interchanges, we'll travel around the world for other unique examples.

Three-Level Roundabout in England

This three-level roundabout interchange just outside Leeds is perhaps most famous for how poorly it works, causing standstills during rush hour. The interchange was built in the 1970s, and has been unable to sustain traffic loads that pass through the area.

Complete Stack in Los Angeles

This stack interchange is considered a “complete interchange” because it allows drivers to exit in all possible directions.

Nanpu Bridge in China

This bridge interchange spirals upward before providing an exit. These interchanges are often used on steep terrain, or when the approaching road terminates too far from the end of the bridge.

Interchanges: diverse as the challenges they solve

As we’ve seen, interchanges around the world are as varied as the challenges they solve. Different solutions are better in certain conditions. It’s through the ingenuity and vision of highway designers around the world that we're able to keep moving from one place to another.

About the Author

Scott Hotchkin, PE*, is an SEH highway design professional who has designed more than 70 interchange projects across the country. Scott is often called upon to help decision makers determine the appropriate intersection design treatment for their particular site and community.

*Registered Professional Engineer in CO, IL, IN, IA, MN, NE, NC, SD, TX, VA, WI

*Some images may contain unusual visual distortions resulting from Google's mapping software.

.png?width=113&name=SEH_Logo_RGB%20(1).png)