At its core, the National Environment Policy Act (NEPA) mandate is simple: Before federal agencies (and the involved public or private partners) can put a shovel in the ground, they must evaluate, document, and report on the potential social, economic, and environmental impacts a project may create – keeping public stakeholders informed throughout the development process.

In brief, NEPA is about transparency for the public. It’s about making sure those in decision making roles serve as “trustees for succeeding generations,” specifically, in protecting and nurturing our environment.

But what triggers NEPA, and what are the project consequences of ignoring this law? Does NEPA in fact produce better projects? What does the process entail? Let the following FAQ and downloadable and printable NEPA decision-making tool serve as your guide.

What is NEPA? Why is it important to the public and private sectors?

NEPA was signed into federal law in 1970 – setting the long-term stage for environmental policy for public and private projects in the U.S. It is a procedural statute that requires federal agencies to work through several steps while evaluating all potential social, economic, and environmental impacts before construction can begin.

NEPA applies to all federal agencies and their actions – “actions” meaning projects, policies, permitting, as well as regulations and licensing. NEPA established the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) to oversee process implementation and make sure federal agencies meet their obligations.

What sets NEPA in motion?

Federal funding! The NEPA process must be followed even if just $1 of federal money is allocated. Once federal funding is involved, the lead federal agency sets in motion, conducts, and is responsible for seeing the process through. The lead federal agency can and often does delineate tasks, but everything filters up through them.

The NEPA statute applies to a broad range of federal government actions, including:

- Issuing federal regulations and policies

- Providing federal funds to public and private projects

- Making federal land management decisions

- Issuing federal permits/licenses/approvals

- Other federal undertakings that may result in the potential for significant environmental impacts

What are the consequences if the NEPA process is ignored?

The consequences of not adhering to NEPA are severe and long-lasting. The responsibility of conducting the NEPA process (outlined in detail below) falls on the lead federal agency. As a result, the consequences often hit them the hardest. However, they distinctly impact private developers, communities within which projects are being planned, and all other involved parties. These impacts include:

1. Damaging lawsuits. The NEPA process is enforced by a “citizen suit provision,” meaning anyone can bring a lawsuit against the federal agency responsible for violations. If a federal agency allocates funds for a specific project and, for example, the private developer moves forward without waiting for the NEPA process to close, the federal agency is liable. But lawsuits impact all involved parties; they begin with an injunction that immediately halts any in-progress work, taking significant time, effort, and attorney and court costs to resolve.

2. Say goodbye to funding. If anyone puts a shovel in the ground for a given project before the lead federal agency has completed the NEPA process, funding may be denied. Funding is a pain point many communities and private developers face; taking action before the NEPA process is carried out in full can put your entire project at risk.

3. Lengthy project delays. NEPA non-compliance creates a cascade of potential project delays, including public discord and intervention, lawsuits, review agency intervention, the need to completely redesign a project, and NEPA documentation re-writes, among many others.

4. Public resentment. Those who ignore NEPA often spark resentment and lose trust with the public and involved agencies/stakeholders. Choosing to neglect the process means they have chosen to neglect the environment and their commitments to resolving a community’s or developer’s needs.

Public awareness and engagement are key to NEPA compliance. Here, we see SEH staff involved in various types of public and stakeholder outreach.

How does NEPA produce better projects?

Environmental laws like the Clean Air Act inspire excitement because they’re tied to specific outcomes (e.g., eliminating or reducing pollution). NEPA, on the other hand, is a procedural requirement and can feel like a time-consuming obstacle. But the reality is that NEPA plays a critical role in producing better projects. Here are four ways:

1. Reduces timelines and budget risks. Studies by the CEQ have shown that projects that start the NEPA process “after” decisions have been made often result in public and private stakeholders seeking “litigation-proof” documents – increasing project development costs and lengthening delivery times.

2. Demands accountability. The NEPA process undoubtedly protects, restores, and enhances natural resources and our built environments. How? Providing public officials, resource agencies, and other stakeholders with valuable information and creating a formal opportunity (mandate) for decision-makers to take a hard look at potential consequences of a proposed action.

3. Minimizes adversity. NEPA encourages the inclusion of mitigation commitments, which help project leaders avoid and/or minimize potential adverse project effects.

4. Public and stakeholder buy-in! Showing the public why the project is important socially, economically, and environmentally lays the foundation for buy-in from day one.

Let’s get technical. What does the NEPA process entail?

The NEPA process involves a lead federal agency responsible for conducting the process and ensuring compliance. The lead agency is usually determined through jurisdictional authority and may include:

- The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) for most highway projects

- The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) for levee and flood control projects

- The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) for airport projects

- The Federal Transit Authority (FTA) for transit projects

There are times when more than one federal agency may be involved. In these cases, the agencies serve as joint leads, or one or more agencies, while the Department of Energy (DOE) may serve as the cooperating agency.

When the government proposes a new dam or bridge, or when a private company seeks to build a pipeline that needs a federal permit, NEPA requires the lead federal agency to take several steps before breaking ground:

- Analysis, documentation, disclosure and consideration. The lead federal agency must conduct a study detailing the project's purpose. They must then consider a range of solutions and provide rationale on a preferred alternative solution/plan for the project, the potential consequences of the preferred alternative (social, economic, and environmental), and measures that can be taken to reduce or eliminate harmful project impacts.

- Public and agency engagement. The lead agency, in partnership with the private developer or community where the project is taking place, holds public meetings/hearings with open, meaningful stakeholder and agency participation and involves local experts in the project’s development.

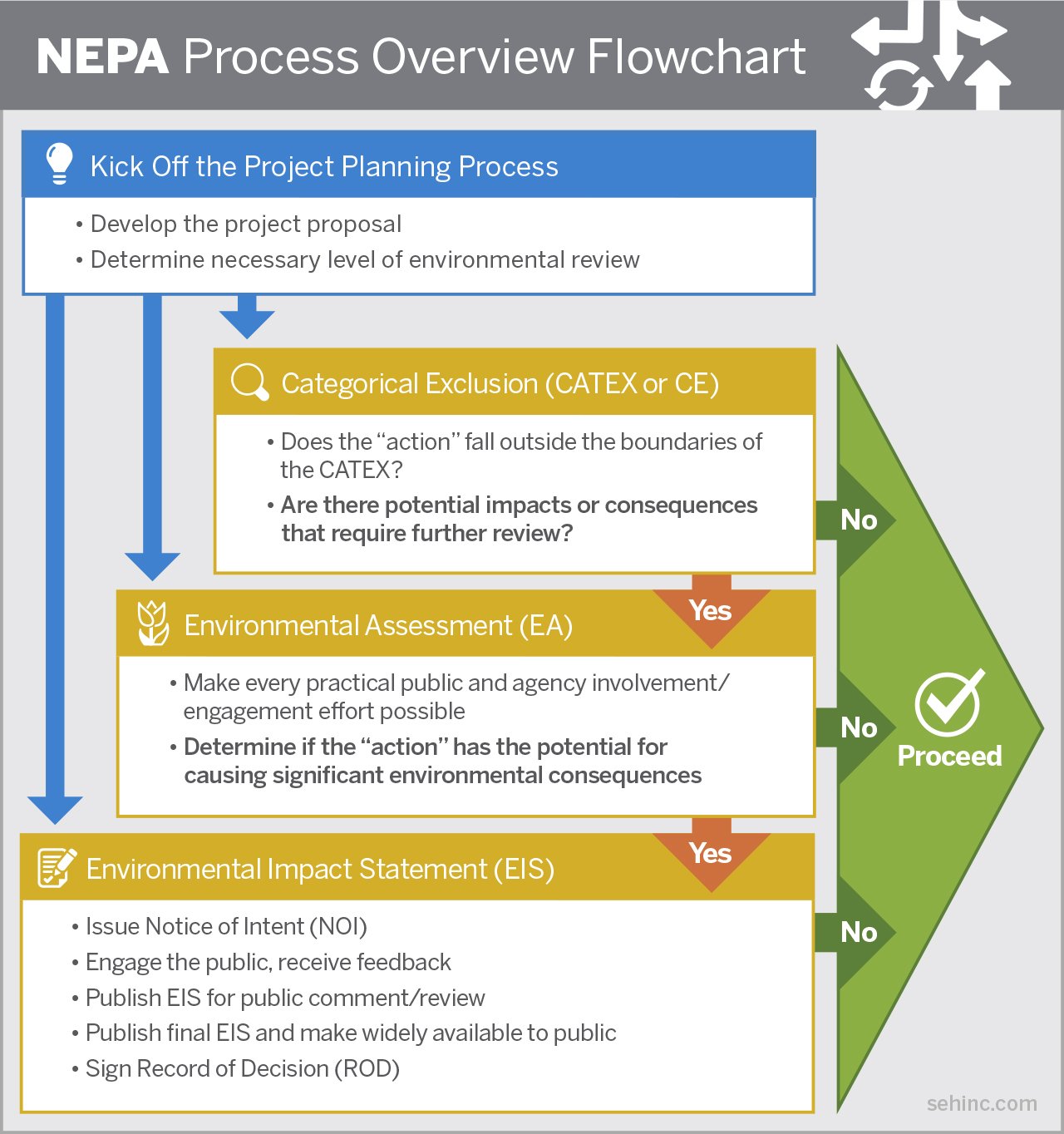

- Reporting. Unless the project qualifies for a categorical exclusion (CATEX or CE) because of its low environmental impact, the lead agency needs to conduct and distribute one of two reports: an environmental impact statement (EIS) for projects with potentially significant impacts and public controversy, or an environmental assessment (EA) for projects where the impacts are less significant or controversial. Specialists often conduct these reports (expanded on within the next section) like SEH.

The following flowchart highlights each step in the NEPA process. At the conclusion of this article, you’ll find a complimentary in-depth decision-making checklist and tool that can be downloaded, printed, and used to make sure your projects are continuing in the right direction.

I want to know more about the different NEPA documentation options...

There are three primary categories of review and documentation as part of the NEPA process:

- Environmental Impact Statement (EIS). NEPA requires the lead federal agency to prepare an EIS for major federal actions that could greatly affect social and economic conditions or environmental quality. An EIS is a detailed analysis of the potential impacts of a proposed action and the range of reasonable alternatives. Public participation is an important part of the EIS process.

- Environmental Assessment (EA). When the need for an EIS is unclear, an agency may prepare an EA to determine whether an EIS is needed or to issue a Finding of No Significant Impact (FONSI). An EA is a briefer analysis. The process requires opportunity for public consumption, comment, and feedback. The federal agency leading the process will approve the findings based on the information within the NEPA document and take into consideration public or other agency comments. The findings are called a Record of Decision (ROD).

- Categorical Exclusion (CE or CATEX). Projects that anticipate no significant environmental impacts call for the less rigorous CE/CATEX to be prepared. It should be noted that NEPA does not prevent nor replace state environmental reviews. Several U.S. states, including Minnesota and Wisconsin, have state laws similar to NEPA and require their own review and documentation on certain projects. Colorado and Iowa, among others, do not have state-specific environmental protection regulations.

About the author

Darren Fortney, AICP, is a transportation planner, SEH Principal, and senior project manager. Throughout his 25-year career, Darren has successfully completed over 100 NEPA documents. His expertise includes comprehensive knowledge of environmental/NEPA processes and documentation, agency coordination, and transportation planning.

.png?width=113&name=SEH_Logo_RGB%20(1).png)